— 1. When arguing, seek to understand context —

[Published 2016] Roughly between ages 13 and 23 I was thoroughly convinced that best thing an intelligent person could do is to get obsessively good at evaluating and crafting sound arguments. Rationality! Debate! Wisdom! I rearranged a lot of my life around that wishful ideal: that any obstacle can be solved with a sufficiently sophisticated argument. The past 3 years or so have convinced me that I’ve been fundamentally mistaken. Let me try to explain why: 1. An argument, however sophisticated, is always constructed within some context. (A therefore B, assuming X, Y and Z…). 2. The moment you start getting invested in the arguments you’re constructing, you begin to get blind to the world outside of your context. It’s like how you tune out everything else when you’re trying to perform a precise task. [2b. If you’re earnest, you might try to have a model of not-your-context. But it’s always going to be simplified because of cognitive limitations… as well as some more subtle, insidious reasons. To get a little ahead of myself, every in-group has an oversimplified model of its corresponding out-group. To go a step further- if you MUST argue, it’s prudent to start by trying to model your opponent’s context, as accurately as possible.] 3. When you get it right, you’ll get tremendous validation from other people who share your context. This feels very, very good, and is very, very habit-forming. [3b. This is so habit-forming, in fact, I think it’s outright addictive. I think once you get into the habit of fighting for your in-group, you begin subconsciously looking for opportunities to fight for your in-group. There are few drugs as sweet as peer validation. And it’s not necessarily a bad thing; a lot of the greatest things about humanity were motivated by peer validation.] 4. Sometimes you’ll win over people who are in adjacent, overlapping contexts – and these few instances are held up as glorious victories. You will cherish these. But these people were usually more or less already exploring your context to begin with. To put it very crudely, it’s like hunting docile rather than wild animals. 5. Once you start hanging out with people in the same context, there’s a sort of natural radicalization that happens. It’s not malicious; it’s almost ‘physics’ – the most attention gets naturally funnelled to the most egregious mistakes made by people outside of the context. So there’s a sort of ‘gravity’ that ‘pulls’ everyone closer to the ‘center’. The most radical members spend the most time in it, influence it the most, etc etc. 6. Now you have an in-group and an out-group. This is almost always bad news. The “sound arguments” are now almost entirely subservient to the group needs. The gravity is too strong, it bends the light, and almost nobody realizes this. The people who do realize this will typically be ousted from the group, or quietly leave themselves. More radicalization. 7. The primary way each group interacts with the other is by focusing on the absolute worst outliers of the other group. As SMBC said, “every group is some % crazy assholes“. Every group in turn holds up the outgroup’s crazy asshole as a sort of threatening bogeyman. (Of course, this doesn’t mean that all crazy assholes are equally bad or not-bad. Some crazies cause serious harm to other people.) 8. When a ‘normal’ member of the group encounters the other group, and gets caricatured as the bogeyman, their response is naturally to get upset. They might try to argue for a while, but whatever argument they come up with, however sound or calm, can always be framed as “lol why u mad tho”. You can’t argue your way out of that one, the only way to win is not to play. (Or to win some other game OUTSIDE the narrow context you’re currently stuck in). 9. The vast majority of each group then ends up being highly suspicious of one another. As a result, they end up barely ever having real conversations with the other. Their contexts are so different that they might as well literally be speaking different languages entirely. (And in fact, if you pay careful attention, they always are. Every in-group develops its own language.) 10. The only way out of this mess, as far as I can tell, is to avoid labels, avoid in-groups, and to try and make sense of each issue independently. Don’t let your in-group identities precede you. And always be wary whenever you find yourself trying to argue with someone. 11. The challenge with #10 is to genuinely, legitimately suspend judgement. You do this by realizing that your judgement is necessarily limited because it’s formulated within a specific context, and that the world is always bigger than your context. 12. If you’re good at doing 10 and 11, you will cease to be surprised or shocked by things like Brexit or Trump or any other supposedly outrageous phenomenon. The surprise mainly happens because you’re heavily invested in your context – the friends you talk to, the media you read, so on and so forth. 13. Let me try to return to the starting point – why I think I’m mistaken. 14. I used to believe that the way to winning people over, to making friends, to earning respect, receiving validation, serving the world, etc – was to get really good at debate, at arguments. The idea there was that if you get good at it, you’ll get closer to the truth. 15. The reality of it, however, is that you get very good at a very narrow subset of things. You just don’t see it because you’re so focused on it that the map becomes the territory for you. You become the person who understands the map better than anybody else, but then someday you’ll follow your map right off a cliff – because the map isn’t the territory, and it can never be. 16. It is much more difficult – and far more useful – to learn to identify the context that you’re in, and to ask yourself if that’s the context that you actually want to be in. If that’s the best context for you. 17. It’s exceptionally difficult because it requires relinquishing the validation that you’ve been conditioned to enjoy from arguing on behalf of your in-group. It requires (at least it did for me) a sort of self-imposed exile. In my experience, this is actually harder than quitting smoking. And it makes sense that it would be. 18. Actually, come to think of it, a lot of the frustration, ennui, listlessless, etc that I’ve faced in the past 3-4 years has been largely caused by discovering that so much of what I had invested myself into was really some narrow game or other. Consider, for example, once you’re an adult, how silly teenagers seem when they get all caught up in their drama. 19. To the teenagers, of course, it’s not silly at all. Their context is all they know. If you mock your child for being frustrated by his “trivial” context (when you’re being frustrated by your much larger context), don’t be surprised if he decides that you don’t understand him. Because you don’t. TL;DR: Contexts, man. Context is everything. Everybody’s is different. Yours will change sooner or later whether you like it or not. When you recognize this, you don’t need to argue so much. But of course you can’t force this perspective down anybody’s throat. Also – arguments aren’t bad things. They’re tools. The important thing is to use the right tool for the job.— 2. To disagree constructively, seek to understand context —

[Published Jan2019]The way I see it, often what makes a disagreement interesting is whether or not the other person has a sense of vision. A lot of twitter idiots (from every subculture, tribe, ingroup) have no vision, which makes the disagreements hideously boring – unless you’re somehow able to entertain yourself in the process of arguing with idiots.

All communication is lossy and involves trade-offs. A good faith discussion and/or disagreement is sensitive to the fact that the other person has made those trade-offs. “Ha, your communication is lossy!” is so uninspiring. It’s the opposite of inspiring; it’s dispiriting.

One way to think in terms of makers and critics. You shouldn’t have to be a maker to be a critic, but if you’re going to be a critic, you ought to be a constructive one. “vision” here is a sense of possibility, an idea of what good would look like. A critic that just goes around saying “this is bad” is worse than useless, he has a chilling effect on makerspace. [Some nitpicking is useful, most of it is trash.]

A disagreement is interesting if both parties make an effort to show each other what they each see, and to try and see where the other party is coming from. It’s uninteresting if one party is just mindlessly going “boo, no, ew, ick, weak, stupid, bad, fail”.

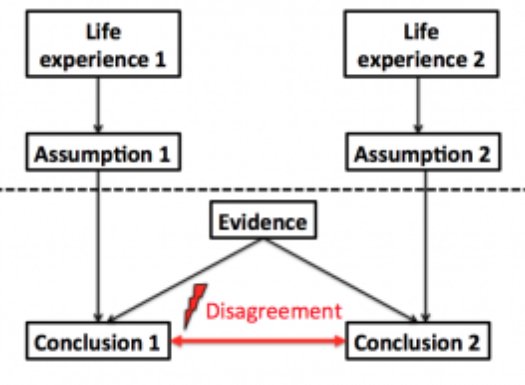

Here’s another way of looking at it. If we have a disagreement, we need to identify our respective assumptions, and talk about our respective experiences. if you’re not open to doing that, then don’t waste people’s time by disagreeing with them stupidly!

“But that’s so much effort, why should I waste my time doing that?”

Because that’s how you make friends. that’s how you build relationships. that’s how you expand your mind. So in my view, you’re actually wasting your time if you’re not doing that, and instead having shallow disagreements that you don’t learn anything from.— 3 —

(dec 2016) different perspectives are more kaleidoscopic than different “points of view”

Thought: Words and phrases like “perspective” and “point-of-view” don’t adequately convey how radically different people are. We aren’t just looking at different things from different angles, we’re looking through entirely different lenses, shaped by different chemicals and contexts. Even if I actually come around to looking at your point-of-view, I won’t quite see what you see or think what you think. For example– suppose if you put a rich man in a poor man’s context- say a prince sleeps on the streets for a night- he won’t experience the full depth of despair that comes from legitimately not knowing where his next meal is coming from. Worse, if he’s not careful, that narrow experience can give him a false confidence that he now understands how it is. It’s interesting to think, then, about how there are many kinds of ignorance. The first is solipsistic: you assume other people don’t exist, or exist merely as extras in your life- as entertainment and annoyances. The “let them eat cake” ignorance (she never actually said that, by the way!) The second is presumptuous: You take some trouble to get to know somebody else, maybe look through their Facebook feed and blog and think you have a pretty good idea about who they are. Which seems to work well… until it doesn’t. The third is humbling: you come to realize that everybody, including yourself, has the capacity to surprise you. That life is an endless mystery, and that everything that you think you know is really just layers upon layers of low-resolution maps and models. These maps are often inherited, outdated, rarely verified, and always vague to a degree that you do not realize. And yet somehow, despite all of that, we manage to function most of the time. It’s really quite fabulous. The most fabulous thing. We may never truly know what it’s like to be one another. But it’s a pursuit that’s endlessly rewarding, and I think it’s worth a try. — 4 — People typically have high-res models of their own lives and lower-res models of other people’s. We are all born clueless with incredibly low-res models of the world – then we tweak and upgrade our models. Different people do this to different degrees depending on many variables Cluelessness, innocence, naïveté, privilege – these are all words used to describe the condition of having a flawed and/or low-res model of the world. A child who loses their innocence is forced to develop a higher-res model of some harsh and ugly things A common source of misunderstanding is as follows: a person experiences an increase in resolution of their own model of something that’s relevant to them. They then make a claim based on that model that extends beyond it. It might seem accurate to them! People inadvertently do this all the time because natural language is fundamentally fuzzy&vague. We say things that seem true to us, but may only at best be true in the context of our model, which is vague to a degree we cannot appreciate until we get a more precise, hi-res one What does this look like? A person has a bad experience. He then makes a general statement that extends beyond that experience. This statement contradicts someone else’s experience. Boom, we have ourselves a conflict One way of avoiding this is to caveat everything endlessly. “It seems to me in my experience under X circumstances that…” – but this is tedious and tiresome. (It’s a good habit, though) Here’s an example of someone who thinks he’s developed an insight based on his experience, and makes a general statement that extends beyond it. It’s interesting to consider that his statement must have genuinely seemed true to him when he said it. Why?